The following is a speech I gave at the Cadillac, MI Pride, yesterday (August 22, 2015). Cadillac is a town about two hours away from Grand Rapids by car. Its population is about 10,000, although it serves as a hub for rural, outlying communities. Thank you so much to Karen Prieur, David Roosa, Tiffany Robinson, and everyone at Cadillac Pride for having Teri and me out!

The bandstand was actually right on Lake Cadillac, with the audience facing the water. Which was really pretty!

Good afternoon! My name is Mira Krishnan, and I’m so happy to be visiting with you today from Grand Rapids. I want to ask you to share a little bit of your time on this wonderful day with me, to talk about what Pride really means, and what it means to embrace and celebrate, instead of fear or loathe, diversity. To do that, I’d like to start by telling you just a little bit about my personal story. I could go on for this entire time about me, but I do that a lot. Rather than just talk about me, I want to tell you about me more briefly, to provide you context, and talk about some other things.

Probably some of you in the audience today know a trans person. But, I’m guessing, many of you have never met one of us before, or really gotten to know us. That’s important. We know that a majority of Americans who know a trans person – 66% – support trans rights, but that only 16-20% have met us*. That does make me an ambassador, because I want you to join the “know a trans person” group. Don’t worry, if you’re already there, I think I have a few things for you, too.

I represent one trans story. The story I represent has a simple moral: being trans can be a wonderful thing. Although, like most trans people, I “knew” since I was little, I didn’t come out to anyone until just a little less than two years ago. That first time, I was really aware of the risk that coming out entailed. I practiced what I would say. I didn’t sleep all night after that first time I came out. Similarly, coming out to my company was scary. Coming out to my parents was scary. But for me, what magically happened, is every single person of importance in my life, embraced me. Every single one. That really meant something.

I went fully public in July of last year – it’s just been 13 months, and it has continued to be like this – not only does no one object, but over and over and again, people tell me that they understand me better now, feel closer to me. I see in their faces that they take pride of ownership in my success. Good people – and I believe most people are good, with some occasional help – they use the way they respond to new situations as a way to learn to be more good. That kind of unanimous, unambiguous support and love has really changed a lot of things for me. It’s been what some people call a virtuous circle: as their responses got better and better, my coming out experience got simpler and simpler, and more and more authentic. In the Bible, it’s written as, “Iron sharpens iron.”

Thanks to that kind of support, I don’t doubt if I’m a woman any more. I just am a woman. I don’t use apologetic or defensive language. This might be new to you. For me, I reject the notion that I am now or have ever been anything other than female (and nobody really argues with me). I’m not almost as good as anything; I’m amazing. I wasn’t born in the wrong body; I was born in just the right body. And I don’t apologize for being trans – I rejoice in it. That first night I came out, I planned and I planned, and I thought about all the details. Now, when I come out, it’s pretty much, “I’m trans. Get over it.” And people do! That comes from people not just accepting me, but embracing me.

And that means I get to focus on things that really matter, and say, maybe surprisingly, that being trans (in contrast) is actually kind of boring. Let me take a quick pause there. One theme that comes up, over and over again, is allies asking for education. I love that. You might feel, though, at this point, I’m not educating you, because I’m not talking about all the “stuff” – hormones and medications, gender marker changes, surgeries, clothes – that you think of, when you think of transness. This is not mistake nor oversight. You think you need to know the wrong things. Unless you’re trans, or a healthcare provider or close family member helping a trans person make decisions, this stuff really is not what you need to know. That’s like, when people want to get to know black people, my friends point out, we always want to, you know, touch their hair or know how they make their hair look like it looks. That’s really, seriously, don’t be touching people’s hair, it’s creepy, but it’s also wrong-headed, because what they’re telling you when they’re saying not to touch their hair, is that that’s not how you get to know them. Talking about this “stuff,” is not how you get to know us. I am telling you the important stuff. And it is kind of boring, because although there’s a richness in our trans experience, we are diverse creatures in a diverse world.

Let me tell you what’s not boring!

So, you might ask, what isn’t boring? Let me tell you what isn’t boring. For me, personally, I’ve gotten to spend the last four years building a world-class Center for Autism, at Hope Network, my base camp for changing the world, back in Grand Rapids. We get to change kids lives, and we’ve been building life changing therapies at a quality level you just couldn’t get, and often still can’t get, around here. And I’ve gotten to help waves of young clinicians develop their skills – not just creating dozens of full time jobs with good wages and benefits but building and launching dozens of careers.

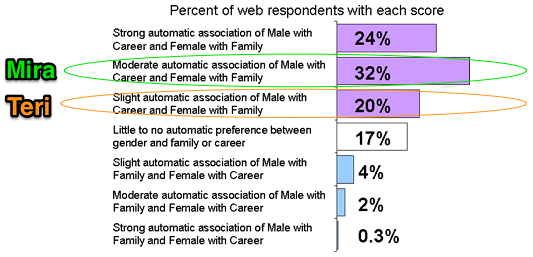

What else isn’t boring? Right in the beginning of my coming out process, wobbling still, as I walked in my true identity, I met Teri, my Prince Charming. I got to see that, at least once in a rare, rare while, love at first sight is real. And although everlasting love can take work, we’re up for it. Last summer, about this time of year, Teri came out to me, as a trans man. That makes us the strangest hetero couple maybe you’ve ever seen, but I say also the cutest. Two months ago, he proposed, and I look forward to spending happily ever after with him, although you know, that’ll be a lot of work, because happy ever after is something you’re not totally just given – it’s something for which you fight.

And finally, what else that isn’t boring, my advocacy life has blossomed. I don’t have to advocate for feminist movement while denying my own womanhood, any more. I’ve made so many friends in the women’s and LGBT movements. I’ve gotten to speak alongside amazing speakers, and like everything we do out in the community, feel like, when I get invited to talk to people, I learn so much that I’m the one getting away like a bandit.

That’s my trans experience. It’s not a lot of things. I don’t represent all trans people. I’m what we sometimes call “binary” – meaning my identity fits much more closely to the male/female gender binary than some people’s do (I’m a feminist, radical down to my roots, so don’t worry, I rock the boat a little too, and I challenge for sure all the things people say girls and women can’t do). But, people tend to react to me with, “Well, if you’re trans, whatever that is, it doesn’t sound very interesting,” and I recognize that I evoke that response more than a lot of other trans people. But while non-binary identities, genderqueer or gender fluid people, may seem more “exotic” to you, they’re actually really cool, regular people, too, and I hope you get to meet them, and they’re not as different or other-worldly as you might fear. For all the things my trans experience is not, my trans experience shows one thing I need you to know. That one thing is: being trans, and loving a trans person (like my guy), can be delightful. Not just survivable, not just okay. It can be a privilege – I’m lucky to get to be who God made me, and I’m lucky to get to love who God gave me to love.

Trans people, before, during, and after they come out, can live joy filled lives, and when we embrace them, and give them room, sometimes they can really fly.

Beautiful cinema vérité moment – performer dancing with two little children wearing Pride tees. This is actually what it’s all about. Little kids get it.

There’s a catch. What’s so important about this event is that what can happen is not what always happens. You knew that. You didn’t need me to say it. But I am saying it. This relates closely to the next thing I want to talk about: a much broader notion of diversity, within our LGBT community and allies, and also a much broader notion of what it means to advocate for a world that embraces gender and sexual diversity, and finally, a broader notion of Pride.

A big part of the reason my life has been so great, is something called privilege. Privilege is all the things that make my life easier, but I didn’t earn them. Privilege, for me, is coming from a middle class, highly educated family, which meant that I very naturally slid into being highly educated and affluent, myself. Privilege has always kept me in safe neighborhoods. Privilege means being able to access the best resources, easily, whether they’re anywhere here in Michigan, or anywhere else in the nation or the world.

Privilege is a big part – maybe the biggest, but not the only part – of what makes my life so easy and so wonderful. And I didn’t earn it. This is the first kind of diversity I want to talk about. Opposite privilege – that advantage I didn’t earn that makes life easy for me – is marginalization – the disadvantages that I didn’t ask for, and I don’t control, that make my voice less hearable and block my agency.

I started this by telling you about my privilege. If you’re familiar with this idea of privilege, and particularly if you’re, oh, I don’t know, white, straight, male, maybe you might be surprised that I’m the one talking about my privilege. And you should turn to the person next to you, who’s not straight, and get them to notice, too. That’s right. A lot of us the visible, hearable LGBT voices come from highly privileged gay people.

This is why you’ll hear more and more outspoken advocates in the community, like me, shift and balance so that we’re not just talking about, say, trans rights, but we’re also talking about how black lives matter (even if we’re not black). We’re talking about how, and to whom, and when they don’t matter. Which is precisely why we need the #BlackLivesMatter movement. This is a big change – you look around Pride events, and usually, there aren’t too many Latino or Black faces in the crowd. That’s what happens in Grand Rapids. That’s what happens, entirely too often, throughout LGBT community. And if we’re really talking about a world where gay people matter, then we need to be talking about gay people who are Latino or Black. To give you an example, you might have heard about the epidemic of violence against trans people. This year, we believe twenty hate murders in the US have occurred, already, and there’s a quarter of the year left. These are hate crimes, although the law doesn’t always recognize them that way (here in Michigan, it doesn’t). What you may or may not know, is that here in the US, the lives lost are almost always black and Latina trans women. So if we’re real about ending this, we have to be more cognizant about this. We have to realize, for instance, I’m not the one whose life is in danger – even if that statement isn’t always popular among my non-Black/Latina trans family members. You hear this same story again and again – the vast majority of all violence against LGBT people motivated by intolerance of their gender/sexual identities, is against black and Latino LGBT people, and we can’t fix that if we’re not honest about it.

The other major shift we need to make is talking about poverty and how it relates to the LGBT community. The visible image of us, all too often, is a limited image of a small segment of us – you know, the stereotypical young, pretty, toned, gay men on a yacht. They have a lot of disposable income. They know all the best places to get brunch**. They’re the kind of person your business wants as a customer, and the kind of person you want as your new gay best friend. Right? I mean, yes, I know people who actually fit that stereotype (and I fit too closely to that set, myself). But that’s not a representation of the whole LGBT community. While many of us have high earnings, many more are highly impoverished. They might have the education, the talent, the skills, but they can’t get the job. Or they might have had their chances cut off way before all of that, when they were just kids. And here in Michigan, where you can get married on Saturday and fired the next Monday for being LGBT, that’s a big deal.

Cadillac Pride, and Prides like it, are particularly important, because we’ve got to recognize that every queer person does’t live in San Francisco or Manhattan or London. Right? We’re everywhere. The Network brought Pride to Grand Rapids, from Washington, D.C., a little less than 30 years ago. Because it turned out that there were gay people in Grand Rapids, too, not just big cities. And that same message goes to the importance of not just the legacy they left us in Grand Rapids, but what you are building here in Cadillac, and also how we reach out to all those little communities up here, you know, the ones that think of Cadillac as the “big city,” and look at you like you’re city slickers? Yeah, it turns out, they can be gay just as easily as you or I can. But they can’t get resources as easily as we can. And we need to support them better.

The second kind of diversity I want to talk about is what it means to truly embrace and celebrate people who are different from “us.”

At the Network, in Grand Rapids, in partnership with MDCH and organizations throughout Michigan, one of the exciting things we’re working on is talking about LGBT wellness. We’re starting with smoking cessation. What? Well, smoking kills more LGBT people than hate does. And while there are still people out there who do hate us, the tobacco companies love us. They’ve been studying for decades how to get minorities and gay people to smoke and keep them as loyal customers. You know, like, to the grave. It’s time to remind them, we don’t die easy. And that’s just a start in a broader message that we have to take care of our own community in order to be able to take care of our towns and cities. At the Network, you’re going to hear us talk more and more about health and wellness for LGBT people. At the Grand Rapids Community Foundation, we launched Our LGBT Fund last year, with more than $350,000 committed so far. What are we going to do with it? Help support the most vulnerable LGBT people. 40% or more of homeless youth are LGBT or questioning, and it’s time to say NO MORE, and engage to help families of LGBT youth stay intact, help parents through their children’s coming out, end the practice of kicking kids out of the home because they’re different (this isn’t some hypothetical situation – it didn’t happen to me, but it did to my fiancé). And if LGBT youth do become homeless, these are kids who hold our society’s future in their hands, not refuse to be thrown away, and even though they’re more likely to be homeless, the system often doesn’t accept or help them, because they’re different. We’re going to put an end to that.

Those are two different takes on diversity. Here’s a third. Back to Pride. Be proud. Don’t come up to me and apologize – I don’t want to hear it, and I’d much rather be your friend than hear your apology. Yes, I, like a lot of LGBT people, I do struggle with being one of the “lucky” ones, survivor’s guilt. But I’m here. And you’re here, and you’ve made a choice to be a part of this family. Be proud of it. Whether you’re gay or straight, Pride belongs to you – it’s a birthright – if you are invested in a world that celebrates difference instead of fearing it. And although the sexual and gender diversity you straight people bring to the table may not be as visible as what we bring to the table, diversity belongs to you, too. Being heterosexual is a sexual orientation. Being cisgender is a gender identity. It’s okay to own yours, even if it isn’t like mine.

So thank you for giving me the opportunity, especially those of you who’ve never met a trans person before, to let you get to know me. And please, stay in touch. Come talk to me and to Teri. Connect with me, if you’d like, online – my blog is at miracharlotte.com and you can even hear Teri and I tell a part of our story in an audio excerpt I’ve got there from StoryCorps. You’re very welcome to find me on Facebook, etc., too, and stay connected that way. And please keep being a part of embracing pride in gender and sexual diversity, and making the world better for all of us, straight or queer, by making it more inclusive of all of us. Thank you.

* I said 61% from stage, sorry! Well, the numbers are approximate, anyways.

** Right now, it’s TerraGR, people. But that’s really not the point of this story.