Our Everyday Chance to Politicize Our Purchasing power

I saw this video from Fusion Network, on Facebook, and it made me think about how many choices we make, every day, that we don’t realize have direct links to class warfare and the devastation of poor or developing communities.

In fairness (not to Monsanto, but to reality), the situation is more complicated in India among small farmers than being solely driven by Monsanto. Mother Jones provides an excellent summary of research on this topic, demonstrating that GMO crops are good for large, heavily industrialized, commercial farms, but bad for small Indian farmers. Which actually (since there are those who get angry and rush to defend Monsanto and the rest of big farming) amplifies the situation, because there are known harms of big farming that are not directly linked to Monsanto*. By, erm, well, exposing the panties we wear, the video highlights how intimately the damages of industrialized farming touch us, but it also teaches us a decision we make — what, a few times a year, maybe once every month or two? — is tied into a larger political context. Of course, all the other clothes besides our panties, and obviously, the groceries we buy, play large roles in this, but it emphasizes that, just like we choose to recycle, we choose to limit overconsumption, we choose to take energy saving actions, we have meaningful choices to act in humanitarian ways, when we do consume, as well.

This provides additional context to something I already knew about — I knew about the farmer suicide crisis, and I am attuned to, but admittedly don’t make purchases regularly based on, the dangers of big farming. But it re-emphasizes for me how small purchase decisions add up — last year, we went through this with a big purchase decision, in that we decided early that I didn’t want an engagement ring that meant that some kid in Africa had lost his arms in the blood diamond trade. There are more and more options emerging to avoid this, but we liked the idea of an old ring as a solution, and the one we found, from 1760, older than the Declaration of Independence, made before Jane Austen was born, fit the bill. In this case, I ended up with a ring that I love more than I could ever have imagined loving any jewelry.

Getting to spend my life with Teri is what matters, not any ring…

Just last week, we were dealing with our furnace, which had broken down due to a problem for which Carrier faced and settled a class-action lawsuit**, and a news article that showed up on Google News, about Carrier driving jobs out of the Midwest to low labor foreign markets came up.

The thing is, I really, really like being warm.

Which makes me ask, who is being devastated so I can be warm? In the case of our furnace, we had the lawsuit-related work done, and we didn’t find downstream damage at this time, and so we decided to keep it. We did pro-actively get two quotes yesterday, and one more coming on Monday, to know what our options are. It had occurred to me only that the relative merits of continuing to use a 93% efficiency furnace from 15 years ago (because a lot of the environmental harm from products comes from creating them in the first place) might outweigh the benefits of jumping to 96% efficiency in a new furnace, but it had not occurred to me, again, that my decision was not loosely tied to class politics but much more directly tied. Interestingly, even the National Review is angry about this, although, predictably, they see a conspiracy in green company stimulus, on which Carrier “dined and dashed” in accepting these funds and later moving jobs from Indianapolis to Mexico.

Without having to engage in jingoism, it is true that there has been a huge outflow of manufacturing jobs in the US, and that these jobs were replaced with service sector jobs at much, much lower wages, and often altogether without benefits (source: heritage.org)

Now I perceive the geopolitical questions involved in “American” jobs vs. overseas (or over-border) jobs as complicated, and as I’ve mentioned, after only driving cars, for instance, made inside the US, I currently drive a Prius made in Japan (primarily because of concern over global warming and the link of air pollution affecting early brain development) and an EOS made in Portugal. But it had really not occurred to me at all that there might be salient differences in the employment practices of these companies, even though, for instance, I know like the back of my hand, from my diversity consulting and training work, that certain durable goods manufacturers (Whirlpool and Maytag being examples) see aspects of hiring practices as strategic.

So obviously, I knew about this — I’ve even used this Maytag ad in presentations as an example of the evolution of companies embracing gender and sexual diversity (source: Maytag)

The point isn’t that I’m better than other people when I succeed in thinking about these things, or that I’m worse when I fail to think about them, but more that these opportunities to politicize our lives and our voices are actually all around us. When we stop and think about them, we’re cognizant of them, but in my case, I haven’t trained myself to think quickly enough about the implications of my choices in the everyday.

And while people bemoan things being politicized, I want my voice to be politicized. Because, back to Fusion’s point, there’s so much more at stake than panties. And even if they aren’t going to save the world, how I talk about how I buy them, who knows? It just might.

* One thing I want to be fair about is that there is a lot of rhetoric in this conversation, particularly around GMOs and claims of direct health harms that have not really materialized. I am mostly concerned here not with the possibility that the GMO food you might eat (or wear) might make you sick, but with the probability that the farming practices used to make it are making communities and countries sick, economically.

** Of course, this also generated response pieces like this one — for what it’s worth, our furnace is diligently inspected annually, and all the HVAC people we spoke to about the problem agreed that, in their experience, this was a design issue with the furnace and not primarily a care / maintenance issue.

Embracing Feminism Young and Old

An interesting juxtaposition of events occurred, Saturday, and of course, it is precisely these juxtapositions that contextualize experiences, and in the best of times, help me learn to use them to be a better feminist.

The beautiful Hope College campus (source: Flickr @Leo Herzog)

I went to Holland, MI (my hometown) to see a production of Vagina Monologues at Hope College. Hope is a well-regarded, albeit socially conservative liberal arts college, affiliated with the Reformed Church in America, a mainline Protestant church. The Monologues are needed at Hope — when I was in high school, I attended special programming for high school students there, and later, I also took two Hope classes before I went to Michigan (Russian and Calculus II, an interesting combination). So it was never my “home,” but I have been thankful to be its guest many times — and irrespective of the form of its policies, I have felt pretty welcome when I have been there. Even back twenty years ago, in connecting with students, particularly in environmental action, I remember learning from young women at Hope their concerns about sexual assault and a general atmosphere in which women did not feel safe on their campus. And yet, the Monologues have played there for years, but this was the first time that Hope “allowed”* them to be performed on campus.

This year’s production was directed by the granddaughter of dear friends. That grandmother, herself, was involved in the production of the Monologues a generation before, and this presaged other intergenerational feminist moments the Sisters on stage shared. That made it deeply special, in a whole other way besides seeing the justice of this play finally airing on campus at Hope, these voices finding wind on those grounds. The production she directed, the art that she and her friends and colleagues created, was brilliant — it married Monologues both old and new** with the ferocity of young feminism in 2016. It was cutting, reflective, considerate, angry, funny, sad, joyful, hopeful, worried, and all gloriously at the same time.

After the play, Teri and I went out for drinks and had an amazing, intergenerational feminist dialogue. We got home a bit before one in the morning. Back to the juxtaposition I mentioned, the second event then happened, when I came home that night, by way of seeing posts on my Facebook timeline (I first heard of this from my fabulous and inspiring friend, Lizz Winstead). It was something I really expected never to see: Gloria Steinem letting Sisters down by saying things that were frightfully wrong. There are really hardly any people alive whom I respect like I respect Gloria Steinem, and prior to that night, I didn’t even consider such a moment possible.

You can watch this, for yourself, above (and also read Ms. Steinem’s subsequent apology). This is not a call out nor even a call in to Ms. Steinem, not primarily. I don’t feel at all qualified to do anything of the sort. This is also not the important conversation about idolizing Sisters in movement, and forgetting that they are human beings*****. My position on the Democratic primary (the young feminist comment occurred in the context of support for Bernie Sanders) remains that I will fight hard for the winner, and I appreciate the (usually) respectful dialogue and engagement in problem solving that is being generated by the Primary. I don’t even have much to say about the equally awful things said about trans women in the conversation.

All I want to do, at the moment, is talk about my experiences being around young feminists.

I have been engaging with young feminists a lot — locally, in informal and formal settings, and online — and what I saw from this fierce group of young Sisters (and from the men and others, as well, in the room) mirrors my experience with young feminism. Tumblr doesn’t really work for me, and although I have an account there, my primary online experience with feminists is Cuntry Living***. I’ve been learning there, from feminists half my age and even younger. To my delight. Seeing them, or hearing this production at Hope, leaves no doubt in my mind that the future of feminism (not that I’m passing my torch anytime soon) is in very good hands.

Young feminists are fiery. They are deeply, naturally, unaffectedly inclusive — approaching the very dream we all have, as represented by the dream of Martin Luther King, Jr., that one day his children and “their” children would someday play, side by side. For young feminists play, side by side, and true play is always glorious. Young feminists are intersectional in a real, true way — they are learning, as I have been investing in learning, how to move beyond white intersectional feminism. For them, feminism is so much more clearly and artlessly a way they talk about the web of kyriarchical oppression, and I love that they are finding not just ways to ally and advocate for those who are oppressed outside of girls and women, without denying their womanhood or the concerns of our sex, but a way to make this their lifestyle. They are reflective and introspective, both when they are not, and when they are, loud and proud. They are so brave in melding their personal, lived experience, the fount of feminist authority for all of us, with the broader issues that affect us all.

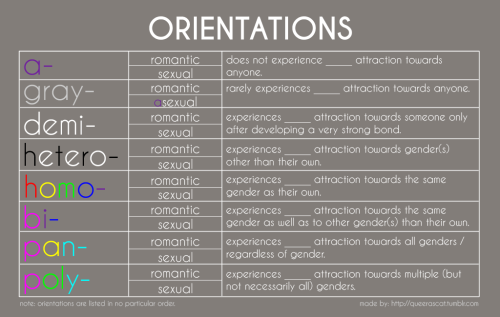

There are challenges, to be sure, that young feminists face. One, I think, is that the young feminist movement, alongside the young queer movement, shows a tendency right now to engage in what, to me, seems like a very taxonomical, classification-oriented approach — this can be seen, for instance, in Tumblr graphs of sexualities or genders.

Source: Tumblr @queerascat

What I want to, gently, say about this, is not that all these identity states are not important (they are!), or that advocacy around them is not important (it is — for instance, one of my ally priorities this year is to educate myself about asexual/aromantic people by way of being a better ally). My concern — gently — is that down the road of this kind of approach is the challenge that understanding feminism, or understanding queer theory is really not well suited to the approach of memorizing tables of information.

In young feminist discourse, this often means that, quite separately from content notes or trigger warnings (which have their own complicated politic), there is an intense classificatory urge, that I see in the discursive system (and in which I participate, myself), when I am around young feminists, to label or assign things — as transphobic, as biphobic, as heterocentric, as cispatriarchical, as sex-worker-exclusive, as classist, as ableist. Identifying our prejudices and biases, our internalized self-hatred, and problematic**** views and mindsets is so important. But sometimes, I see reticence to have in-depth conversation about the processes at work, beyond just applying the labels. This is where the danger lies — for this to be the end point and not the beginning point of feminist process. The process, in a way, mirrors how we use social technology — this blog post itself is tagged and categorized, and hashtags are a kind of taxonomy, and these kinds of taxonomical processes really underwrite much of the explosive capability of these tools to get activist information out in people’s hands. But, again, to me, and I say this gently, I think a Future Feminism (more on my thoughts on Future Feminism) that stops here (which young feminists have not done, but which will be a challenge down the way), that limits itself to classifications and tags and categories and markers, will not be enough, and although it will spread information among the educated like wildfire, it will not teach or nurture or build up subsequent generations of feminists.

These challenges mirror the challenges of every generation of feminism. In many ways, they are far milder — they are not the racism of the first wave, or the heterocentrism of the second wave, or the gender essentialism of the third wave (or wave 2b, you know, I’m trying not to be overly classificatory here). They are challenges nonetheless, and they belong to us all — not just young feminists as defined by chronological age.

I think the very discursive system in which we argue about whether “young feminism” or “old feminism” is better to be deeply problematic. To me, one of the most beautiful things about being a feminist woman is that I have so many mothers, so many sisters, and now, even so many daughters in movement. Like when I work with young children, my goal in support of this future generation and their future feminism is not to tell them what to dream, or even how to dream it, but to support them in acquiring the tools they need to push feminism farther, to dream their own dreams, and to bring those dreams into reality. That is a privilege — not in the acknowledging one’s privilege sense, but in sense of honor. I want them to be good feminists, but I do not presume to know what a good feminist is, nor do I presume that I measure up to that moniker. As a mother in movement, I expect to be uncool at times. When I was young, this was where we made our parents drop us off a block from school so that our friends wouldn’t see us kiss them goodbye. And although I engage in moments to teach what I can teach, I learn, also, and I truly do receive far more than I give.

To see our relationship as “old” feminists not this way, but as a form of seniority in movement, will be disastrous. We will not win tomorrow’s war with yesterday’s weapons. We will not build a sexism-free, an any-ism-free, future, with the tools of the patriarchy. This is my opinion — not my dogma: we cannot think hierarchically about young and old feminists. We have to be unafraid to learn more than we teach, as I have always done when I am around young feminists. We have to stop dictating who wears the mantle of authority if we wish to abolish mantles of authority and the privilege they confer. Put very simply, I will make no one free if I say to them, “You belong to me.”

I spoke with the grandmother of the director the next morning, about other things, and we touched on this issue, sharing our very positive experiences working with feminists younger than us (since she is a generation older than me, and I am a generation older than her granddaughter), how we are inspired and draw energy from our work alongside them, and how we work hard not to control but to nurture them. And that, ultimately, is what I want to say in response to Ms. Steinem’s comments. I just want to share my lived experience, a middle-aged woman who is proud to stand among young feminists.

Notes:

* We all ultimately are allowed and disallowed, although we are all ultimately freed not by others, but by ourselves. So whoever stamped the approval, those young women took their rights, for rights are not truly given.

** The Vagina Monologues is a living work, and over time, vaginas, or monologues, as you wish, have been added, and their voices lifted. Notably, the Monologues of today bring voice to Sisters who might not have been heard when the play was created, including trans women and ethnic minority Sisters.

*** I’d love to settle the score on how CL is represented in the press — I will do that another time, but for now, I will just say that my experience with CL so much differs from what is claimed about it, that when I read about it, it is barely recognizable to me.

**** By problematic, one typically means throwing someone else under a bus for one’s own sake.

***** It’s noteworthy here that I already crossed a threshold of disagreeing with something bell hooks said, likewise, not something I had expected myself to be doing.

Really Embracing People with Mental Illness

Self-disclosure is scary, and we’re taught not to do it. Sometimes, that’s the right call – one study I read suggested 85% of physician self-disclosure in care was not helpful to the patient. But it’s important to just talk about the experience of being ill, particularly when other privileges mean I might get taken more seriously than some of my siblings, and particularly when it’s the experience of mental illness. In my case, that experience was with anorexia, which started around 2001 and tailed on and off over the next several years (“pulling myself up by my bootstraps”), followed by progressive, fairly steady recovery after treatment (in Chicago, in 2008-2009).

An estimated half of the population will never experience mental illness of any kind. Far fewer will experience an eating disorder, specifically, and none will know just what it was like to be me, since my anorexia experience is not like your bipolar experience, and it is not even, truly, just like other anorexia experiences. So, you may not understand “us.” For we do still become an us, for people with mental illness experiences are a marginalized group, of sorts.

That 85% statistic – it arises when self-disclosure is really to make me feel better. That’s where self-disclosure goes wrong. I’m not posting this for me. I’m posting it for all of you who will never know what this is like.

This is my MMPI profile. I took the test eleven years ago, in the winter of my first term in psychology graduate school, at the University of Florida, at the age of 29.

My MMPI-2 taken just over eleven years ago, during my first year in graduate school.

I’m not going to tell you everything about how to read this. The short version of the scales on the left is that I didn’t have a biased responding pattern – I told it like it was. In the past, at many psychology programs, it was actually a requirement (dating back to the intermixing of psychoanalytic blood into psychology) to not only take the MMPI but undergo psychotherapy with a faculty member, and that MMPI would actually be used clinically on the graduate student. There is so much wrong with this that one scarcely knows where to begin. At Florida, we were asked to take it, but we could fill in whatever responses we wanted, and no one saw our MMPIs but us. But in my case, I wanted to see what it said, and I was honest – navigating the thin line between covering over my flaws and making my problems out to be worse than they really were.

The good stuff is the right-hand side. Ignore scale 5. It basically says, “She’s a girl.” That reveal hadn’t been done, yet. For the rest of the ten scales on the right, scores above the red line are called “elevations,” pretty much just like any other elevated lab result. Of the nine scales (ignoring the girl one), six are elevated. That could be interpreted as being pretty bad news. By general practice, this much elevation in an unbiased profile is worrisome.

There’s a lot to the profile. Some have commented that young women seeking psychological help actually have this pattern not uncommonly – in fact, it almost seems like it’s a young-women-figuring-themselves-out scale pattern (at least in our culture and time). Some choice statements about the profile – that I may be trying to change the way the world perceives me (very true, in those days), and that women like me “tend to approach problems with animation, are sensitive, and feel that they are unduly controlled, limited, and mistreated” (okay, yeah, so it’s like you KNOW me… and thank you for the Oxford comma).

So don’t say, “Well, these numbers didn’t represent you.” They did. I was pretty sick at that time, and I was certainly trying to figure myself out and trying to deal with a world that thought I was things I was not. On all sorts of levels. Although I made so many new friends in Gainesville, the loss of stability of living in one state for all my life was significant. My diet was restrictive, and although I was stabilizing, and I made a conscious decision to be ready to be able to take care of patients the next year (no clinical work in year one), I had gotten to a point where I was always hungry, I had lost so much fat that my back hurt sitting in hard chairs for very long at all, and food scared the hell out of me. I would be done with purging – I may even have been by then, but if I had, this was a brand new accomplishment. That bit about becoming paranoid under extreme stress? Yeah… ummm, that happened a couple of times, that year. There were other times, sadly, and this is kind of a statement about graduate school, that my paranoia was not paranoia at all, but well-founded and cross-validated fear – and since I know this facet of how I work, I am sometimes overly conservative in admitting that I am not being paranoid and that, rather, my fears are justified and my persecution is real.

I pulled up a 2008 study of women who had midlife eating disorders. My profile wasn’t totally standard – in particular, somatic distress was much higher in most of them, whereas it wasn’t an issue for me, really (I sort of trooper’ed through when my back hurt, for instance). The mean profile , a 2-3 combination, is different than my 6-7 – my highest scales were much more elevated than the mean participant in this study. Other data, though, including anorexic teen girls, was more similar to mine. Meaning simply, that, together with what I mentioned above, this data was actually pretty consistent with how I was doing that year.

There’s more that I’m not going to bother turning into pictures and putting in this blog. Although there are many changes that were part of the anorexia experience that have been permanent, generally speaking, my mental health has been better, most of my life – consistent with this, that old MMPI is very clear that it is short-term distress that is being captured and not long-term personality problems.

There’s a teeny-tiny self-portrait in there.

In the context of that distress, what did I accomplish in the year (roughly) centered on this data point? Well, having been accepted into a world class graduate program, I moved out of my home state (from Michigan, to Florida) for the first time, ever. I completed the jump from engineering to psychology. I acclimated to graduate school and made significant progress towards my Master’s Thesis, as well as making many new friends and doing well generally in my new program. I read dozens of books (for work and play) and god-knows-how-many journal articles. I wrote a novel (I never liked the ending, so it’s been sort of a shelved project, although I hope to figure out the ending and resurrect it someday). I ran my first (and only) marathon (I’ve since run numerous half marathons and a couple of 25k races, although right now, I just run short distances, for fun). As far as my anorexia went, I stopped purging, permanently, that year. I didn’t gain back to a healthy weight for some time after that, but I stabilized, reversing the course of weight loss over the prior three years and stepping away from the rock bottom and ridiculously unhealthy low weight I had hit the prior summer.

Don’t get me wrong. I’ve had other rather remarkable years. But the summer of 2004 to the summer of 2005 is a contender, for sure.

I saved this MMPI profile all this time, and after a number of years (or more particularly, once I was board-certified and there was less potential to use this to discriminate against me), I started jokingly mentioning it in talks I gave. I came across it cleaning up some of my files in storage, and I pulled it out to scan a copy, since it’s something I want to keep. And it occurred to me that it was time to talk about this openly. I recognize it’s truth – that it did, indeed, identify me, but I incorporate all I accomplished that year, because it certainly did not define me in any holistic sense.

No one needs to write a blog about how much someone can do or be or accomplish while they have some physical ailment. It just goes without saying. It doesn’t, for us. And sometimes it isn’t true for us (just like it isn’t always true for them). Sometimes it wasn’t true, for me. But, it’s a single-dimensional lens to look at that MMPI profile and over-infer what the person who holds it could or could not do. You might have gotten her wrong. You might have gotten caught up on what sorry Admissions Committee even let her into graduate school, or point out the obvious, that she’s lucky to be alive (I am, every day). Think of it another way, as a story of the walking wounded. Think of it as a story of resilience. Think of what it portended, that in that time, 11 years ago, she could accomplish all that, for what I can do, now. And along the way, come to celebrate with me, instead of pitying me. For no one ever needed your pity.

On Being a White Feminist (No, Wait, Please Hear Me Out)

I am a white feminist. You guys*. It’s true. I’ve made the argument before that the idea that I function as a woman of color is at best, problematic and defies any uncritical acceptance. I want to go further, now, and point out that I am a white feminist. This puts me in illustrious company – Amy Schumer, Taylor Swift, that actress** who said something ignorant at an awards show, that other one who said something ignorant at an awards show, that other one who said something ignorant at an awards show. Well, you get the picture. And a pretty one, she is not.

You guys, our feminism is WHITE. With just a touch of color over on the far end. Just like this picture. (Source: Unilever)

I don’t actually want to spend this post proving this to you. But let me start with the whitest feminist of my white feminist perspectives. When people say things like, “Can’t we understand that we’re all just people first?” I shut these conversations down, often, particularly recently. I shut them down by pointing out that, precisely because I am a woman, I am messaged in subtle and overt ways, over and over again and since my birth, that I am not a person – that women are not people. The second wave rallying cry, “Feminism is the radical notion that women are people,” was necessary as precisely in that day, because society did not behave in a fashion that suggested it believed this statement, as the phrase Black Lives Matter is necessary in more recent discourse.

This is the whitest thing I have to say, of all the white things I say and all the white things I do – I see myself as a woman first, before all my other identities. This is white feminist precisely because, as I’ve come to be educated, my feminist – even my womanist – sisters of color very rarely see things this way, because race is almost always their most unignorable experience. It isn’t mine. So they’re proudly women, but woman is somewhere lower on their list, most commonly. Often second. In contrast, most of the time, like other white feminists, my race is only relevant in discussing my experience because it privileges and protects me. And like my white sisters, I am more often unaware of it than in any other state. What is important about this is that I am not saying I “pass” for white – I am saying I function as white. These two are not at all the same thing. I benefit from privilege. I did not seek it out.

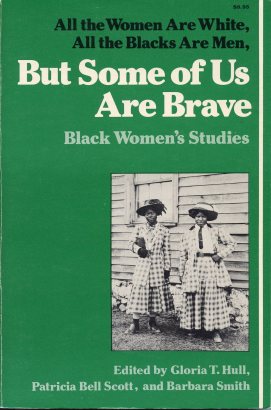

You guys, this is how far our sisters of color have to go to correct the bullshit that we too often call feminism.

But back, for a moment, to my white feminist identity. I say I am a woman first, not because I want all sisters to say this, but because this is how I experience the world. I stop, later, and recognize, yes, I do have a race, and that it is indeed part of who I am. And that I have a class – actually, I am aware of my class more often than my race. But even that is a relative rarity, while I am almost never unaware of how being a woman affects my experiences.

I’m not entirely saying I don’t experience racial microaggression***. Occasionally, other white people – like really, really white people – can make a play to erase my privilege. In fact, last night, I had one of these conversations with a white woman. You know the one. It began with. “You’re so exotic. Where are you from? Don’t say Michigan.” But this not only happens less and less, but it seems to be less and less effective at marginalizing me.

Sisters of color, if you are not already fed up with me, have not already stopped reading, please know this (and continue reading, if you’d like). My goal is simple: I want to help us white feminists figure out how to stop being such a pain in the ass. Don’t be nice. You know it’s true. That is precisely what we are. My goal is to help us be the good Sisters we are meant to be, and not the bad Sisters we have been most of the time. My goal is not to celebrate the outsize space we take up in movement, but to help us to a path to actually allow us to address our misbehavior and stop stealing your space.

Back to my fellow white feminists. Okay, so a solid chunk into this screed, how am I going to accomplish this goal, if I have not turned you, too, off? I think I have an answer. Like all very complicated things, it is also very simple.

We are faced with a conundrum. We are rightly called out for our white feminism. We are told to knock it off. In fact, we want to knock it off. Badly. Erm. We want it badly, but we actually instead do it badly. Here’s why. We replace white feminism with white intersectional feminism. Which, unsurprisingly, is crap. What do I mean by this? White feminism is the queen of all single-cause social justice movements. Its one cause is to help white women feel less worthless all the time. You see, we take up outsize space within movement, and we take up even outsize space in racially mixed groups outside movement, but we take up far less space than we are due in polite white society. And we do, actually, feel worthless, like all the time.

This is the conundrum in which we’re stuck, much to the chagrin of our sisters of colors. We are white feminists because of our experience of marginalization. Our experience, in which race is a source of privilege and not marginalization, begins young. We are not born hating women, perhaps. We open our eyes and see our mother (most of us do), and we love her. She is, in fact, nearly everything. But soon, we notice that the world does not love her, does not value her. And perhaps we learn to hate women by first scorning her as the world scorns her, or perhaps we do not learn to hate women until we recognize ourselves in the mirror. But hate women, we do, sooner or later. And as we are nurtured on the mothers’ milk of misogyny, we learn that we are needy. Overly emotional. We are told and told constantly, although it seems like we try to take up no space at all, we are in fact taking up far too much space. We are told that, although it seems we give far more than everything we have to others, we are greedy for withholding our bodies, our hearts, even our smiles. This is, perhaps, why we sit on the edge of chairs even when they are made for only one person. Because we are not worth the space of one person – we can at most be a fraction of a person, and even then we are inevitably too large a fraction. This is, perhaps, why we paint our smiles on twice, once with makeup and once with the falsity of “putting forth one’s best.”

Our feminist experience then, white feminist sisters, is that we learn this state, we become awakened (often by sisters and sometimes even by brothers of color, who have always had our back in a way that we have not had theirs), and then we band together with others of like experience – that is, other white feminists (because, help us though they did, our experience did not feel quite like the experience of our sisters of color, because, in fact, it was not quite the same). So we bond with other white feminists. And we do get as far out of privilege-borne narcissism to realize that their suffering is like ours, and that the means to our own happiness and theirs are inextricably linked. This is our feminist experience – it is not quite like the feminist experience of our sisters of color, many of whom are taught to hate their race even before, and far more thoroughly than, they are taught to hate their sex.

Kyriarchy, as far as I know, has nothing to do with that annoying 80s song (Source: That annoying 80s artist who sings that annoying 80s song)

Being confronted with the white feminist nature of our white feminism, surprisingly, is precisely where we go most astray. For we are faced, it seems, with two options: White Feminism (capitalizing for the willful practice of foolishness), or intersectionalism. Some of us choose White Feminism. We turn to actively saying things that are destructive. Our feminism becomes a tool of kyriarchy**** and not of liberation. For the rest of us, who would rather die than knowingly put people in chains, the only option we have is intersectionalism. But we don’t know how to stop being white feminists (back to lower case), so we become white intersectional feminists. This, I am arguing, while insidious in its danger, has the possibility of being even more problematic than White Feminism.

The why and wherefore of this comes directly back to how we became feminists – our marginalization histories, and our years of internalized misogyny before we were awakened*****. Sadly, this is the only framework in which we can process the fact that we take up too much space in movement – both in feminist movement and in social justice movement. We do two deeply destructive things in response. They both run deep in us, but for different reasons.

The first, which comes from our marginalization, is that we cover over our need, as we always did before we awakened. We recognize that, in the scheme of things, although we are less privileged than wealthy white men, we are often very privileged. So we place ourselves in a classic old feminine hierarchy, one in which too many of us spent our whole childhood being victimized, deciding whether our pain is of enough merit to voice, and we find that it is not – almost always not. But our silence is precisely what suffocated us before, and it does precisely the same now. And suffocating, dying of asphyxiation, our feminist yearning to survive takes hold, and so even in trying to do this, we lash out. Except now, and precisely because we were holding our breath to try and make space for them (or rather, to try and avoid our habitual stealing of their space) that we lash out at our sisters and brothers in arms. But we know this is wrong, and we hate ourselves all the more for it.

The second thing we do is much like the first, but it comes not from our marginalization but our privilege. We take on the role of Overlady (or Overlord, if your feminism thinks you will be equal when you are a man). I have seen this so many times. White intersectional feminism, unlike intersectional feminism that is not white, is hegemonic in general, like all white feminisms. Its hegemony comes from our whiteness and not our feminism. When she is taught intersectionalism, she “naturally” takes on a conductress role in which she becomes Arbitress of the Intersections. She self-designates her role as deciding who matters more, and who matters less. She silences thus, not just herself, but her sisters as well, for the misguided hope of “giving her voice” to her sisters of color, when indeed, they need not be given her voice so much as she must stop stealing theirs. This, of course, is the prison of internalized and self-policed misogyny in which too many of us were reared – that is, we are leading our white feminist sisters back into precisely the gilded cage from whence we emerged, and we believe it is feminist that we lock them back in the cage and stand guard******.

This is what that Arbitress role looks like when it is held by a dude. Please overlook the grammatical lapsing in my comment, however, which was originally directed to our new Mayor

It should hopefully have become very clear that she does this because she is white, not because she is a woman or because she is a feminist.

We need, very simply, to stop being white intersectional feminists and engage in a more assertive******* dialogue in which we embrace our feminism but learn to undo our whiteness. Our white feminism tries to say, because race marginalization is so much more onerous a burden on others than gender marginalization is on us, womanhood doesn’t matter. That is not a feminism at all. This is not an assault on our sisters of color – only we white feminists say anything this stupid. Note that our sisters of color who reject the label of feminist call themselves womanists. But we create a feminism that liberates others but does not liberate oneself, and this encapsulates, inevitably, that most unfeminist sentiment of all. If I do not believe I matter, then I cannot truly believe women matter, for I am a woman. I learned this years ago but forget it, time and time again, with surprising alacrity.

I become the proverbial empty pot from which no tea (but much hatred) may be poured. But likewise, a feminism that says that race marginalization is not real, or, astoundingly, says treatment by society is better when one is poor and black in America than rich and white, is just foolishness masquerading as feminism. Of all the intersectional feminisms, only white intersectional feminism would make either claim. The problem is not that we white feminists do not occupy intersecting identities, but that we occupy a great many privileging ones, and the still-profound marginalization we experience is due to just the one or two, having to do with our womanhood and femininity, that are not privileging.

We thus cannot simply drop the white and be intersectional feminists, which would be a simple answer and of great service to our sisters of color if it were possible. We do not know how to do this. We might, someday – this would do so much, if not everything, to stop racism. This is because, and we must learn this, race is entirely about the fact that our whiteness makes us “matter” in the kyriarchical system of racism, and the non-whiteness of others makes them not matter, or at least matter much less. Thus, if we could stop being white******** – that is, not stop having a racial identity, but stop having an hegemonic racial identity, then we should undo racism itself, because it is precisely the hegemonic nature of our racial identity that created and maintains racism.

It is not incidental but paramount in understanding the situation, to realize that white is not a single racial identity but a cluster of racial identities into which groups have been privileged, over time, and it, itself – not our skin color but the in-group powers we are conferred when our skin colors are granted the privilege of whiteness, is the source of the hegemonic systems that hurt us and with which we hurt our sisters and brothers in arms.

This is the non-parallel nature of the system. One does not need to learn to stop being African or Latina. But one must learn to stop being white. It actually does operate much in parallel with the hegemonic nature of manhood, into which one is privileged, and the captive role of womanhood, into which one is cast. Just as we have learned that eliminating sexism, even from ourselves, is no easy task, eliminating whiteness, even from ourselves, will be no easy task. One does not need to learn to stop being a woman. One must learn to stop being a man in the hegemonic identity sense, if one wants not to be a tool of patriarchy. African and woman are not hegemonic identities*********. White and man are. We white feminists have a foot in both worlds. The wealthy white feminist is like the child who leads far and periodically darts back to base to tag up and avoid being thrown out by the pitcher for stealing.

I make, dear sisters, a sporting analogy (source: Wikimedia)

What is different about this line of sentiment is that it recognizes we cannot fiat our way out of whiteness nor expect others to do so. It allows us to confront the domineering nature of the discursive system our whiteness creates, while continuing our own liberation as women, and reducing gender-based oppression. I am neither asking us to magically stop being white, nor asking us to accept our whiteness as “the way things are.” So in the end, I offer no magic bullet, but rather a turning into the sharp points. I call us as white feminists to do the hardest thing we’ve ever had to do, and learn how to stop being white, and in this way, and this is precisely why I am recognizing my white feminism, I believe we can learn to stop being white feminists and finally become feminists.

Notes:

* After all, I do say “you guys.” Like, a lot. And like, like, a lot. And it labels me as in group instead of marginalizing me.

** Another post, another time, on why it is not such a feminist victory that we say actor instead of actress, but I will respect the preference of others, and it seems that Delpy uses actress, which is admittedly the term I would also use, were I an actress instead of a provocatrice.

*** And I’m certainly not saying that all my Indian-American feminist sisters are white feminists. Probably most of you don’t feel you are, and the circumstances of my experiencing life in such a white fashion are a complex thing that still remains much shrouded in mystery, even to me.

**** If intersectionalism is the recognition that we operate in intersecting identity spheres that confer on us layers of privilege and marginalization, and that make our experiences, each of us, unique, then kyriarchy is that kissing cousin who reminds us that patriarchy itself is one of intersecting systems of dominance and marginalization that, itself, interacts with other systems, such as racism and classism.

***** Awakened with a kiss, doubtless, this is a white feminist fairy tale, after all, and one reposes gracefully to be woken by kisses in our world. It’s just a fairy tale of the proper, Grimm sort. That is, the fantasy is more warning than pleasant distraction.

****** Right outside the cage door, since someone must be free, after all, and it might as well be me. And we fool ourselves that, because we are in the prison as wardens and not prisoners, we are free, when we can never be free as long as there are prisons.

******* When we teach communication, we teach that there are three principal styles – aggressive, assertive, and passive. A passive style – which is nadir and birthplace of most of us white feminists – is one in which the needs of others matter, but our own needs do not. We know this too well, but our feminism was liberating to us entirely because it exposed this lie, and it will never be a source of liberation for anyone if it returns to it. It is the style of the self-made martyr. An aggressive style – in which our needs matter but those of others do not, is the quintessentially White Feminist style. The white intersectional feminist style tends to be a mixture of the two – passive aggressive. Which you’ve probably been taught is not a compliment.

******** Here I reveal that when I talk about being white, I am entirely talking about privilege, and the harm done to the world because I am given it. I do not aspire to whiteness and claim to have reached it – I find myself stuck in it and am trying to escape it.

********* At the risk of having a ridiculous number of footnotes, there are some rare but notable exceptions to this statement. In the context of exclusionary feminists who operate not in the context of women and men, but in the context of cis women and trans women, woman in their usage becomes a hegemonic identity into which one must be privileged. In general, in this way, Straight is a hegemonic identity and queer identities are generally not, but a like exception in the context of queer women’s culture is when lesbian friends reject a woman whose partner comes out as a trans man, perhaps because he will now have to struggle with having moved into a hegemonic category as a man. I feel like I have to run the risk of footnote perversity and explain this exception, since I was reminded of it by a couple I just met yesterday, who had that latter experience.

Reclaiming the Role of Woman-Identified Woman

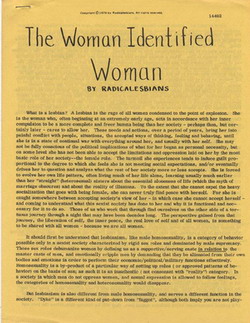

As I was sitting in the conference room of APA yesterday, I remember that back at Convention in August in Toronto, I had heard, for the first time, the phrase, “woman-identified woman,” and I had not had a chance to understand its origin.

The Woman Identified Woman, a pamphlet from 1970, is available archivally to read, at Duke University.

This short piece is worth reading.

It could easily be seen as not only the end of the “lavender menace” controversy within feminism but the beginning of exclusionary radical feminism. I do not think it should be seen that way. It does not translate, perfectly, more than 45 years later. But there is so much truth here.

I have always been a woman. I was not always woman-identified – at times, I still fail to be so. It is the awakening process of feminism that taught me to be a woman-identified woman. It is, in turn, being a woman-identified woman, that gives me any hope that my love, my sexuality, my beauty, or any other part of my self or my experience, may become tools of my liberation and not my oppression.

And yet, it is crucial that I am the only woman who identifies this woman. I am not a women-identified woman, any more than I can be a man- or male-identified woman. And this is where, almost fifty years later, we go farther. We recognize that no woman can define all womankind, and that womankind does not have a corner on marginalization, but rather, we lift women up in solidarity with and alliance with other marginalized groups, and we recognize that both women and people who are not women experience intersecting challenges, and search for a way to be self-identified, just as we Sisters do.

But we continue to recognize that autonomy to create and unmask our own identities, to pursue authenticity, is everything in our journey towards a world without cages.

And in this, I find it so easy to stand in solidarity with these Sisters who spoke before I was born.

A Brief Note on Self-Policing

This brief piece is a response to recent comments by Debbie Wasserman-Schultz, as can be seen here or here, for example. It builds on my call to build an inclusive feminism, as well as to create a culture of calling in, wherever possible (sometimes, it is admittedly not possible).

Debbie Wasserman-Schultz (D-FL) was the source of recent controversy for blaming the loss of reproductive freedom on women born since Roe v. Wade.

In the spirit of calling Ms. Wasserman-Schultz in, rather than out, her statements really help reiterate the importance of teaching the powerful role of self-policing in patriarchy / kyriararchy processes. The system knows that no one will ever guard the cages in which women are held better than the women themselves. The “system” benefits by pitting women against women, because it frees up its resources to focus on robbing our rights from us.

When a woman lashes out at other women – young women in this case (even as young as me, since Roe v. Wade has been in place all my life) – it is not a random act of relational aggression. It is a design of the system. I should like to see Ms. Wasserman-Schultz learn this. I should like to see every woman learn this.

Self-policing is part of what makes these processes like patriarchy so insidious and so difficult to eradicate. A crucial thing for us all to understand is that, because we were born in cages, we do not know fully what the freedom we are creating looks like. None of us has ever seen a world in which women matter – a world truly free of misogyny. We have never seen a world without the cages we are trying to destroy, even when we have broken free temporarily from them. And far more powerful than the bars of the cage is the belief by many caged people – women in our case – that there is no cage, or worse, that the cage is where we belong.

When Ms. Wasserman-Shultz understands this, she will understand that, even when it is true that women are enforcing the patriarchy (which is not at all true of the entire class of women who are under 43 years of age, but in this case, is true of her, herself), we need to educate them, precisely because we believe that women (and every other marginalized group) deserve to be free. And irrespective of everything else (e.g., if she is asked or choses to step down), it is my hope that we all do exactly this for her, and for anyone else who makes these kinds of missteps.

My Evolving Attitudes to Rape (and Women)

One really hard thing to do, I think for a lot of writers, is to go back and see what one said years ago. I want to do just that. I wrote this piece…

What was on my mind the Summer of 1996, which was my Junior year at Michigan.

…just a hair less than twenty years ago. Half my lifetime. I suppose I could wait until it actually turns 20 to critique it, but it’s on my mind tonight, because we finally have the time to watch The Hunting Ground, an important recent documentary about #RapeCulture. And this is what I was thinking about, just as I was old enough to legally drink, while I walked the streets of one of the college campuses discussed in the film, and if I was “lucky” not to have been a victim, this was the world I lived in, nonetheless.

A lot of things change in twenty years. I don’t want to put myself on trial. I just want to be honest with myself – and to get a better idea of how my thinking has evolved over time. So, I dug in and read what I had to say, back then.

Going back and reading something I wrote, particularly on a topic like sexual violence, sounded (and was, to some extent), cringeworthy. The backstory is that, at the time, I was briefly the Editor-in-Chief of a libertarian news magazine. Four years earlier, I had done one of my high school volunteering projects supporting Bill Clinton’s campaign. But my position was Libertarian, at that time.

I defend elsewhere, ironically the last time I went and found something I wrote twenty years ago, why I had and in some sense still have a relationship with libertarian philosophy. But I mentioned that I was briefly Editor-in-Chief. My tenure was very short, precisely because of the huge divide between classical liberals and social conservatives, and the fact that the paper was losing all its classical liberals, one by one, and all the replacements showing up were social conservatives. I have never – even in those days – liked social conservatism, although then and now, I am friends with social conservatives. Anyway, I continued to be liked and actually supported in not being a social conservative. I wasn’t kicked out. I stepped aside graciously in recognition that they had a groundswell and “we” did not.

I was actually relieved. I was not a total jackass in those days. Although I continue to emphasize my statement that men needed to be included in the movement to stop rape, I understand this in a much more nuanced way, today, and now I get the need both for safe spaces and that far from being an “anti-male” issue, men needed to be included precisely because we women need them to, well, clean their shit up. I will have to own some internalized misogyny – I was not then the female chauvinist I am now. I hadn’t been ready to acknowledge the obviousness of marriage equality. Although I was aware of the issue, and in a backhanded sort of way, I applauded them for talking about sexual violence inside the LGBT community, I wasn’t a supporter of marriage equality, yet, in those days. That did change, obviously. So I will have to admit to some internalized queerphobia, too. I am proud that I was beginning to understand intersectionally – I was paying particular attention to conversations on the intersections between race and poverty and sexual violence. And at a much more basic level, when sisters were saying that rape was a violent crime (in those days, there were a lot more people who thought about it in a primarily sexual way), I was paying attention. I am embarrassed, however, that I thought in those days that the Contract with America or any of the other GOP proposals to “reform welfare” had anything to do with addressing the issue of poverty.

And these days, although I am functionally somewhere in between Christian and “spiritual but not religious,” I probably would be way more likely to lead a prayer to Artemis than object to it. Because, you know, I love my female role models.

I will have to settle for not having been a total jerk.

Flash forward to today, and I am sure I am still fairly full of internalized misogyny. There is work, yet to be done. I hope that I am a better listener to women who’ve had experiences different than mine. I hope I advocate alongside them in a better, more trusting, and more supportive way.

And of course, twenty years later, rape on campus has not been addressed. Take Back the Night has emphatically not lost its relevance. And, in my imperfect way, I will continue to bear witness. I will help these stories get known, help these experiences get talked about, and help these changes get made.

Managing Conflicts Among Women

I wrote this piece, about eight months ago, and I gave this speech, about six months ago, as way stations in my progress towards articulating* my thoughts about how we respond to confrontation within feminism, and confrontation generally with other women. I’m still working on this line of thought. I probably will be forever. This is just another way station. A somewhat lengthy one.

I need to start with a couple of disclaimers, and everyone knows I hate disclaimers, because these things I am talking about are not sins at all, and I am deeply unrepentant of them**. The disclaimers do, though, lead to the heart of the matter.

The first is that I wish to talk to, with, and about other (moderately to very) feminine women. Yes, this is certainly a conversation more about femininity than about womanhood. Yes, there are butch and masculine women. Certainly I am their great fan (certainly, they make my heart go pitter-patter, although it turned out that it belongs to a man). Although I see guilt-voices from other feminists chiding me to then speak of “femininity,” and not “womanhood,” I respond that, here, I talk about feminine women, both because I do not entirely, yet, understand the entanglement of womanhood and femininity, and because I really do not presume to speak on behalf of feminine men. I am not of them, nor to have spent great time studying them. They might tell me I am describing them as well as myself. Feminine women, too, may tell me I am wrong. But this is a significant part of what feminism is about – it is discovery of the bounds of the invisibly gilded birdcage in which one is made to present both beauty of feather and of lilt. There are feminists who believe her freedom is found in casting off her femininity. I am not one of them. I wish to help her embrace her femininity and create a world in which she can be both free and authentic. So let me dispense with that, sisters.

A whole bunch of women (and three men) who are not talking about feminist stuff. Source: Reddit

The other disclaimer is that, when I talk about confrontation among women (who may or may not be Sisters), of course, not everything every woman says*** is feminist. Obviously, right? I mean this isn’t news. Look, you, at the the women of Fox News (who occasionally might get it right, but frequently get it wrong). Look at Carly Fiorina. Extending this obvious point, though, is perhaps a more subtle one: there are disagreements between women that are not grounded in feminist principles, and for these disagreements, feminism may provide groundwork but not substantive resolution.

But in this, the sister is damned if she does, and damned if she does not, and now we are getting somewhere.

She is damned when the disagreement is feminist, damned in a million traps laid for her. She is hard pressed into forms of logical discourse that may or may not apply well, to feminist theory, and more particularly, which encapsulate sexism in that they favor strongly masculine thinking styles over feminine thinking styles and masculine knowledge over feminine knowledge. I’m not saying that women nor femininity are inherently illogical – they are not. My scientific credibility is not in conflict with my femininity – but these rules and processes are built by men and for men, to operate in a world of men, and I am saying this as a feminine woman who has spent great time and effort acquiring this knowledge, both from other women and directly from men. To this point, too, these processes also favor the knowledge of the enfranchised over the knowledge of the un- or disenfranchised, a thing we see over and over again in phenomena like mansplaining and whitesplaining. And thus she finds herself damned into conversation that amplifies all of the disparities she opposes in the most deeply moral ways imaginable to her kind, and as her adversary is likely pressed into the same type of conversation, she is double damned.

She is damned, too, and perhaps less overtly, if she does not. My observation is predicated firmly on observing myself (and learning, over decades, to not see this as a flaw in myself). It is necessarily generalizing, and it is not meant to invalidate the examples of sisters who differ in these particulars. But for a moment, I want to speak to what I suppose, are many woman besides myself. We have no love for fighting. In fact, we hate it. When we choose to use the didactical tools of the patriarchy, we, like men, are somewhat able, although I suspect far less completely than them, to depersonalize our conflict. Certainly, when we fight men, they will tell us to do so. And damn us, we try. But our fighting is inherently far more personal, I believe, than theirs. This can be seen in archetypes and stereotypes – particularly the archetype scene of the two men who pummel each other with fists, and running out of endurance, lying on the ground together, find healing. These men then arise and drink beer together. Because their fights, even, surreally, when they seek to physically hurt or even kill each other, are not very personal.

This is not how fighting among women seems to work, at least not in many of the scrapes into which I’ve gotten. No, our fighting is deeply personal, it is scarcely anything other than personal. Contrast against that example of the men in a fistfight a prototypical way that a woman has fought with violence: by throwing herself into the gears.

Probably not completely unique to women (and feminine people in general), but more pronounced, on average, among women, is a tendency that needs consideration here. Even if we do lash out, we also lash in, and this is important. The gears stop, but against our bodies are exacted a terrible price. In a funny way, my history with anorexia is a good example – I would get caught up in self-starvation, the mental health problem that could most double as a political statement!

My observation (and particularly my introspection) reveals that our anger almost always is deeply enmeshed with guilt, self-doubt, and self-loathing. This makes our fights very different from fist fights, and it makes our very notion of victory, in the best of cases, very different from what other kinds of victories look like. Think about this: when was the last time you felt good after conflict, and particularly when was the last time you felt good after conflict with another woman? If you’re having trouble finding even one example, think about all those times when you didn’t feel good. Perhaps you “won” the fight, but that victory was deeply pyrrhic for you. Inside the Sisterhood, “white feminism” demanding an erasing solidarity probably works entirely based on this subconscious or even conscious knowledge, for all of us, that there are no knockout punches in our fights, and we will never walk away unhurt, nor really even feel any strong sense of having won. Often times, sisters back down to other sisters, for this very reason, although this, too, is pyrrhic, in the self-loathing engendered by allowing (what we believe to be) wrong-minded views to flourish.

Rose McGowan, whom I love, recently picked a fight that should be addressed (because she was right about almost everything, but what she was wrong about made all the difference), but not in a way that just hurts all the sisters involved. Source: Wikimedia

I am coming to believe, buried in this, and probably at a level at which we are rarely cognizant of it, there is some kind of fear that there is evil in us, evil that works in a morphology like dark magic, where once it is unleashed, it is not re-bottled, and it will consume us. Society is all too willing to reinforce this idea about us, from the witch trials, to the very idea of hysteria, to the celebrity-gone-mad storyline****. Although not uniquely told about women, these are all strongly gendered messages, and ones we internalize in our self-hatred as well as recast onto other women.

Thus, we find we scarcely know how to fight someone else without fighting ourselves, and although we may be mortally afraid of others, in ways, we are always more afraid of ourselves.

And thus, although our fighting is deeply personal, deeply sensual, focused not so much on weapons nor damage, but far more on tooth and on nail, it is powerfully violent in a whole new way that fists could never be.

This is interesting. If the prototype of men fighting is the fistfight (something I suspect very few women have ever done – I certainly have not, in any event), it is worth noting that this kind of fighting is optimized not to inflict severe injury. Think about our bodies and think about how fighting looks (the stereotype on television will work). There are certainly places on the body (such as the base of the skull) in which a relatively smaller force could be lethal. Men in the stereotypical fistfight do not hit each other in these places. In fact, this is seen throughout animals – rams head-butt each other in a way that involves a fight that results in a winner and a loser, but which relatively less frequently involves anyone killing anyone else. Now guns and knives change this, significantly. But the point is that the culture of fighting among men (and certainly, they have spent time creating such a culture, over many, many generations), is optimized in a very different way than the culture of fighting among woman has been. In primitive society, strong solidarity was far more crucial to the safety of women than men, and being cast out was likewise far more dangerous to women than to men.

Echoing this, over the millennia, although incarceration certainly primarily affects menfolk, broadly, there is a pronounced emphasis on casting out when it comes to the treatment of women – adulterers, sex workers, and other women of “ill repute,” single mothers and those not deemed appropriate for pregnancy, and many others.

We echo this, as well, in our discourse. It is a part of the reason why we argue about whether other women are feminists, in a way that men would not do (instead, typically arguing that he is wrong, or more broadly, stupid). We do not have old boys’ clubs, or really a direct equivalent, but we do have amorphous but pervasive networks of social power, and many of us rely on them in far-reaching ways. And they are networks from which women are far more commonly cast out, a thing for which the old boys’ network is not renowned.

So we have a different brand of fighting, often, among women, with different stakes. In some ways, these stakes are far more precarious, and rather than analyzing the ways we fight each other as women by comparing us to men, we should understand how these ways have evolved over time to be most damaging to most women.

Now what?

First, if we buy into this line of reasoning, which is admittedly here in a rough draft form, then, we should see that making fights among women more like fights among men will not solve anything. Certainly, most of us don’t have any real interest in throwing punches. But even when we consider fighting amongst men outside of throwing punches, it is optimized to serve priorities of men and masculinity. It will not be a good fit to our concerns. If there is any level on which we agree that the deeply personal, emotional realm is somewhat emphasized in us as women, we cannot simply shift our fights more into the realm of masculine logic, any more than our fights would be simply resolved just because we held them in Spanish instead of English (or vice versa). Rather, we must complement the development of masculine / agency – driven tools for confrontation with the development of more powerful, but unabashedly feminine / communion driven tools.

Second, such a line of reasoning changes how we understand escalation. Escalation to physical violence, in many of our arguments, makes no sense, and having come this far without using physical violence to solve any problem, like ever, it is not something we are going to accidentally use. Rather, the escalation types, of which we must be most wary, all involve some kind of outcasting process. So if we want feminism-informed conflict among women, we must seriously look for ways to take this, from exiling women from feminism, to exiling women from being recognized as part of what needs to be done in female representation in business or political spheres, to exiling women from our social networks, off the table. While recognizing that our arguments may be deeply personal, and that we may indeed fight tooth and nail, we need to recognize as well, the needs of our opponents to maintain community.

These are pretty lofty demands, and it is still hard for me to understand how I would use them practically when I am in confrontation. But there is power in knowing what needs to be done.

* The book I’m writing, when – not if – I finish it, is centrally about understanding what inclusion issues in feminism teach us about feminism, both as movement and as ideology, and resolving our struggles in-Sisterhood not through solidarity that means silencing those most vulnerable, nor through assisting privileged sisters in drowning themselves in self-hatred, but in a way that recognizes our plurality and focuses on the strength that plurality brings us and the opportunity it delivers to us to build better feminisms.

** I grieve sins, far too many do I grieve, but these are not the sins I grieve.

*** Nor even everything any one woman says, you know, like even if that woman were one we hold sacrosanct within our movement. But certainly not if they’re just some bitch like me. This now being the third blog post in which I’ve dabbled in the footnotes, talking about the idea of using bitch as a reclamation word, and not delivering on it. Who knows, you might have to wait for my book.

**** These stories are far older than Norma Desmond. They have been encapsulated in things like mad songs, almost always sung by women, from ancient times – in proto-operatic forms, the mad song was even a standard component of many compositions, and in my nature of impertinence, although it is, certainly pertinent, I am listening to my favorite collection of them as I write.

An Ode To One’s Spirit

She says the greatest sin is to not live for oneself. You do not understand her.

You say she is selfish and she blushes in gratitude.

Her responses confound you. But in the contradiction, there, you may glimpse her.

Though she alone owns her body, she alone owns her spirit, she sees her self, her identity, her body, her spirit, all these things and more, as a gift to be given freely and richly, and in giving that gift she finds greatest pleasure and greatest sense of self. So give she does, over and over, and her joy and her self both show increase for it. Such gifts that she fashions, which she makes only for herself and gives only to others.

This is her cave of two mouths.

She will allow you passage through her, the truth visible for barest glimpse. She will not force you to know her.

Emerging, you would think it arrogance. But in that moment, that glimpse, you saw, for a moment, that it is not.

The glimpse was fleeting, and it indulges you to slide back out of her, but you will not know her unless you embrace it, unless you remain inside her. So remain you must, and see her truly, for she will show you gladly. She knows no secrets.

And when you do, you who wish to compliment her, you who accept her truth, you will say nothing, offer only nod of encouragement or fleeting smile.

If you remain inside her this long, you will breathe a unity that needs no words, and you will rarely speak of it. When you must, you will say this:

This is she, who dreams of what might be, who prays for what should be, and who creates what must be.