Good evening, everyone, and thank you so much for having me out to speak to you. I want to spend some time sharing with you my story, and I want to use it as a lead-in to talk to you about how we’re re-imagining LGBT community and the role of the LGBT community center, in the Greater Grand Rapids area, and how we need you to be a part of this.

But let me start with my story. Way back when, when I was a little child, I remember very clearly that, whenever there was a choice to do, have, or be things that girls wanted versus those that boys wanted, I always wanted what the girls wanted or had to do. Even when it seemed to most people like the boys had the better option. But right away, I also remember learning that most of this would get me scolded, made fun of, or sometimes punished. The rules seemed confusing to me. I saw girls with painted nails and it seemed to me like mine should be painted, too, but that didn’t go over so well. By the time I was a preschooler, I had a system down to pass as a boy. I wasn’t too good at rough and tumble play, but I liked riding bikes, I learned to like baseball, and then I really took to Lego bricks and building spaceships – people kind of love it when little boys want to build spaceships. Now, I’ve always loved building things, although, as I’ll tell you later, the things I build now are a little different than anything I thought I’d be building back in those days.

In the meantime, over my childhood years, it seemed to me, with the force of everything everyone was telling me, despite what I felt like on the inside, I must be a boy, although obviously not a very good one. So I spent my daydreams dreaming that magic, space aliens, reincarnation, anything, would turn me into a girl, and I imagined all the adventures that girl would go on, the kind of woman she would be, what it would be like to be a bride, but I never thought I could be that girl. I figured out that I could play with the more tomboy girls, especially if there were other boys around, and I could “get away” with that. Every once in a while, I really lucked out, and I found an activity that was mostly full of girls, and I could again “get away” with participating in it. The violin was a major score (some of you can sympathize, if you know how catty and high-strung budding violinists are). Later on, I “got away” with … reading Anne of Green Gables (and later yet, Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte). This kind of stuff helped a little.

My school unselfconsciously used a lot of logos that look suspiciously like they belong to the Black Panther Party. For serious.

My parents moved here, to Holland (I’m a West Ottawa grad) when I was in third grade. That was a culture shock – think back to Holland in the mid-1980s. I felt like, suddenly, I went from having diverse playmates and lots of Indians around to being one of five non-Dutch kids in my school. I joke that me and the Italian-American kid had to band together, and it’s really not so much of an exaggeration. But I learned to hold my own. I learned to have friendships with girls and boys – having female friends was really nice, because many of the ones that became my friends naturally let me into their lives, and while they didn’t necessarily treat me like a girl, they didn’t treat me like a boy, either. I had male friends, too, and I did like some boy interests – my parents let me learn how to program computers when I saw six or seven years old, and I’ve been scripting as long as I was writing, and computers, again, were a great cover, since they seemed innocuously boyish. So I got through. It got confusing, sure. I was supposed to crush on girls, and I was interested in them, but what I couldn’t put into words was that, like them, I wanted – needed – to be someone’s bride, not anyone’s groom. So I dated… maybe one girl in high school. And I didn’t know how to respond to her affection. And I panicked, and although we became friends later, I always felt badly for that. I got fighting the way girls fight out of my system via orchestra – there was this one girl who was always challenging me for my chair, and I took delight in beating her, even though I was playing a $100 violin and didn’t have private lessons.

By the time I finished high school, I kind of understood that there were “Indian Approved Fields” – my parents weren’t keen on medicine, and there was just something about IT that, as appealing as it was (and who knows, maybe I could have gotten in on the bubble?), I didn’t want. So I went to U of M for engineering. I was good at it, too. Really good grades continued to be part of the sham – not that I’m not proud of or identified with my learning capacity, but anything that I could do that seemed to be what I was supposed to be doing … it helped keep up the façade. Michigan was so much fun, too. I wrote for a student newspaper (and briefly was its editor-in-chief). I led an honors society. I met two of my best friends, even today, at orientation, and I had pizza with them at two in the morning and stayed up all night (I didn’t understand all-nighters, because I didn’t really procrastinate in those days, but they seemed exotic, and so I’d pick a class and not do my homework so I could stay up all night with Wei… it was Engineering Mathematics – Fourier equations and loop integrals and stuff – it was really easy and I wasn’t worried about getting it done, anyways). So… I was good at it, but I didn’t have any passion for it. I didn’t date, but I started having really intense platonic friendships with women.

I got exposed to lots of new things in college, that I’d heard of in magazines but never seen before – you know, like English literature majors (my Indian friends swore they weren’t real). I got exposed a little to gender and sexuality politics. There was something alluring about queer community on campus, but in those days, queer was all about being socially non-conforming, and I just didn’t see how that could be me. I’d heard of “transsexual,” but only in the context of the Rocky Horror Picture Show, and I’m just not Tim Curry. I got lots of weird data. I didn’t know other guys who loved Jane Austen like I did. Or who wanted to be pretty and not handsome. People would comment about gender differences, like how men and women sit, and I’d laugh along and yet know I sat like the women did except when I was extra cautious to imitate the guys. So… I made it work. I did Intervarsity, and later Graduate Christian Fellowship. I moved into more applied physics, and I stayed for a couple of years at U of M doing ultrafast optics. And had more really intense, platonic relationships with girls, and one kind of questionably romantic one that broke my heart, also. That was a negative experience on so many levels. I think she recognized that I wasn’t what she was meant to be with… but neither of us had the words for it, and we did have this intense connection, albeit not a physical one really.

By that time, I just wasn’t finding passion in physics. I left to work in engineering. Again, as always, I was actually really good at it. The projects were never quite right, though. I got hired at Ford to ultimately spend two years proving that a technology they’d acquired was a hoax, and working myself out of a job – it was a big win, but I struggled to get an opportunity to try and do something else that would make me relevant to the organization, since they’d hired me (with a great salary) based solely on highly technical skills that turned out to be largely irrelevant once the technology was clearly a dud. In hindsight my leadership was really protective of me (more on this in a bit). I did consulting briefly, but I was terrible at that. I did supplier warranty and then product development. I had a big win, again – I picked up a project that had a five year developmental cycle and had to be started over, more than four years in. I worked my butt off, and I got that part on those vehicles, in working condition, without missing a beat. So I was really a pretty good engineer. And what I did like about it was that it was kind of social – I mean, there was technical engineering, sure, but a lot of that was driving to the plant, spending days at a time there, bonding with the people on the floor, so that when I needed to prototype in a rush or get them to do something they didn’t want to do, they would take care of me first. Plants are noisy and scary (I probably don’t seem now, like I much belong in one, but I can hold my own). Back at Ford, we had a couple of deaths in our plants, and someone died on one of the lines at Textron that actually ran parts that I was designing. On a machine I’d actually operated once or twice on prototypes, myself (because I sweet talked them, and I did their work for them sometimes, and they took really good care of me). That was scary, and it was hard to mourn someone I’d known, even in passing, and support the people I was working with, all with a deadline still looming. I made that work, but during that time, I knew I’d had enough. Masters-degree-or-no, I was done with engineering. I took night classes. Rebelliously enough, in Psychology, because I’d looked at things – I’d actually almost gone to business school – and I wasn’t sure anything would make me any happier.

As Nature Made Him is a really remarkable look at the question of nature and nurture and their roles in human gender identity.

Surprise, surprise, I saw a human sexuality class, and I took it. And… I found out about all kinds of things. I found out about the range of human sexual experience. I tried dating guys, but it was a bust – I was attracted to them, but I was clearly in the wrong place. And I was attracted to girls, sort of. Anyways, I didn’t seem gay exactly, even though (straight) people thought I was gay not uncommonly. Interestingly, the gay guys all knew I wasn’t one of them. I also found out about other things. There was this kid (David Reimer) from Manitoba. Maybe you know this story. So the doctor tried to do this kind of circumcision on him that involves … well, basically, they burnt his penis off. This other person, Dr. John Money, a psychologist, was trying to prove that gender was socially constructed / behaviorally learned. So he told them to basically remove the boy’s testicles, also, and create girl parts, and treat him like a girl. Later, they followed up with hormones. Except their little girl always wanted to pee standing up, and did other things that didn’t really fit. Okay, so this was practical – I started peeing sitting down, and if small, that was vastly preferable. Later, Reimer “transitioned” back to the man he was supposed to be, although he ultimately killed himself, at just a little younger than my current age. This led me to, in turn, find out that there were transgender people. But at that time (this was about 2002), I couldn’t find any examples of happy trans people (somehow, I didn’t find some books that had already been published, like Jan Morris’s Conundrum. Kate Bornstein’s book was about to come out, but that would probably have been too much for my delicate mind to handle. Jenny Boylan’s book was what I needed, but it was still about a year away at that time. I basically drew the conclusion that there was no future in transitioning, and I put it out of mind.

I did ease up on myself. I didn’t come across, at that time, the idea of being genderqueer, but that’s what I did/was/tried. I did little things, like shaving all the hair off my arms and chest, that made me feel less like a boy. I had been overweight, and I really worked on myself, just before this, on losing weight, and as I lost weight, I felt light and airy and … girlish. It became quite out of control – a diagnosable eating disorder, and it probably almost killed me. But, I also connected with other people with eating disorders, and … again, I found a community of women, in which I was largely accepted as one of them (although also flirted on / hit on / etc). And, as I got thin, I got into fashion, and at that time, there were guys wearing girl jeans and so on, and … that was, again, in a very androgynous way, kind of amazing and liberating. But also unsatisfying, because I was still perceived as a man, and utterly unsuited to the role. Like camping outside heaven’s gate, faraway so close, and I was probably at my darkest emotionally in those years. I just didn’t see how I’d have a Pride and Prejudice kind of ending to my story. I didn’t want to kill myself, but I just had visions in my mind of my life… just not ending well. Thoughts of death, yes, but also the fear of living on, for a long time, miserably.

There were other revolutions. I was taking these psychology classes – living a double life as something than the good Indian engineer son my parents thought they had. Okay, this doesn’t sound rebellious to you, but you don’t come from a nice Brahmin family. It’s way more rebellious than it sounds – one of the things that contributed to my parents’ acceptance of me later, is that I have a cousin who’s a symphony conductor, and that “lifestyle choice” is way less acceptable to my family than being transgender. Anyways, whereas I was a good engineer, I found no questions I wanted to answer. I found in psychology, I could solve problems – I was good at that, and engineering education made me even better at it – but they were problems about people. Marie Curie said that, as scientists, we “must concern ourselves with things and not people.” Even though the advice came from a woman, I just couldn’t swallow it. So this was something. So, I applied for and got accepted to a clinical psychology program. I didn’t know what this neuropsychology thing was, that I was interviewing with (… with the president of the International Neuropsychological Society, I should mention, whom I told this), but he was nice to me anyways, and let me come to grad school in spite of that. So I moved to the University of Florida.

Psychology grad school was great for a “I knew by now that I was supposed to be a girl” like me. Engineering classes had one woman for every 7-8 men, back when I was at U of M, but my psychology classes were close to the opposite. More platonic kind of intense friendships. But also I started dating in earnest, finally. I fell in love… I really did feel in love, although I was acting out a character to be anyone’s boyfriend. This was also weird, because she knew about my anorexia, she knew that I liked to wear girl pants if I could get away with it (even if they looked and fit just the same as guy pants, I wanted them because they were girl pants). She mostly accepted all of that. It didn’t work out, anyways, but when I was at the University of Chicago, for internship, I dated with a vengeance – I did eHarmony and went on maybe 25 first dates. I dated one woman for a couple months, and then I dated someone for a year, into the time I moved to GR, to do my fellowship here. We broke up, again, I loved these women, but I wasn’t what they needed, and I guess I did kind of know that. I dated again here – amazingly, I was actually… appealing to women, which was also all very weird about all of this. I settled into a relationship that lasted three years. It was enough, again, to try and make it work. A lot of us think “love will cure me,” and I thought that, too. But it doesn’t, of course. So I tried, really hard, but it just wasn’t working. And living with a girlfriend really meant that I felt like my one space of privacy – not that I was doing anything at home – well, I basically felt like I had no place at all where I could be me, except maybe in my fantasy or dreams. But, I persevered. I took my job at Hope Network, in part to stay here and try to make the relationship work, and in part because it really was a fantastic opportunity (that also almost killed me!).

Finally, after all of this, as she and I were both realizing we needed to move on, I started waking up to the world around me. We live in kind of amazing times. I supported a local theatre company – Actors, go see their plays! – and they did a play called Looking for Normal. About a trans woman. And so I had season tickets, and I took guests to see it. I go to all the plays, so I didn’t know what it was about in advance. And then I’m getting uncomfortable in my seat. I’m looking around to see if anyone as obvious signs of the pitchfork they’ve got under their seat. I’m waiting for the boos and jeers. Except. There aren’t any. No, the play gets a standing ovation. Wow. So I did what any 21st century girl does. I googled. And… I found out the world I’d been hiding myself from. I found Jenny Boylan’s book, and I found out that there were transgender people who transitioned and maintained their social and professional standing. I found out that one of them – Lynn Conway – had an office in the EECS building at U of M, and I must have walked by it a thousand times in the six years I was there, without even knowing she was there. And I found out the modern truth. Transition was not really (for me) inaccessibly expensive. It was safe. It did work. And I could be me without losing things I valued about my current life. I took a deep breath, and as my girlfriend was moving out, I got ready to seriously consider transition. I found a therapist. I came out, for the first time in my life, this is last October – to one of the women I took to the play. She was a lesbian woman who had come out later in life, and who had left behind a significant part of her life to be true to herself. That first night, coming out at a coffee shop, I said something I’d never told anyone in my life – in Chicago, I paid for a therapist out of my own pocket for almost a year, and she helped me so much with my eating disorder, but I never breathed a word about my gender to her. It was amazing. She was gracious. And accepting. And not entirely surprised. I didn’t sleep a wink that night, that had felt like such a revolutionary act. I came out to other close friends. I started therapy. I went to Own Your Gender at the Network, our adult trans group. So I was expecting maybe there would be one or two people there, and they’d think, “You aren’t trans, stop pretending,” or maybe they’d catch me out and put me on TV or something. But actually I walked into a room and saw more than 20 trans faces staring back at me. And gained a sense of confidence. A few months later, I went to First Event in Boston, and if 20 trans faces could give me confidence, imagine being around a few hundred of them.

So, anyways, in December, I came out to my boss. She took a deep breath, and said, in essence, “Okay, let’s do this. We support you.” She talked to her boss, my CEO, a day or two later, and he took a deep breath, and he said, in essence, “Okay, let’ do this. We support you.” And as I kept coming out to people, something magical happened. We estimated losses. Everyone told me there’d be losses. We calculated “acceptable casualties” that my still-vulnerable autism program could sustain. But there weren’t any. I came out one by one to the 50 families we had in therapy by this spring. I’m not going to administer a scale to them, “On a scale of 1 to 5, how much do you accept me?” But the ones that cried with me, hugged me, said, “You do your thing, you’ve got to be you,” or “we kind of know a thing or two about having a child that isn’t anything like what you expected to have, and then it turns out they’re pretty great… if we can do this, you can do this.” I’ll count those as positives. And if they didn’t say anything, just said, “Okay, I understand, thank you, I don’t have any concerns,” I counted them as neutrals. So I had a rate of 70% positive, 28% neutral, and 2% (one person) who responded negatively. Incidentally, that one person got over herself within all of about four hours, and she and her child are still a part of my clinic. I didn’t lose professional contacts either – far from it, networking with OutPro at the GR Chamber of Commerce, I gained so many new business contacts that I scarcely have time to develop them. I got on a plane in February to come out to my parents, and I was ready, if it came to it, to sit on the curb in front of their house and call a cab back to the airport from my cell phone. To get on that plane, I had to be that ready. But they listened, and listened. Then, my dad said, “Okay, but I don’t know why you came to ask us if we accept you. Of course I accept you. You’re my child.” My dad isn’t given to dramatics, this is pretty impressive. And my mom said, “Okay, if anyone in the family has a problem with you, they have to come through me.” That’s pretty par for the course for my mommy – I get in trouble every once in a while, because you really don’t want to see what I’m like if you mess with my kids, and I get that from her. So I didn’t lose them, either When we finally did a staff meeting for my staff, to come out to the ones who didn’t know yet, HR came. I led the meeting. At the end, the HR people said they wished they could go to more staff meetings like this, because my people were so supportive and it was so easy and without tension. Get that – this crazy meeting where your boss’s boss tells you she’s really a girl… it’s the easy meeting.

And… that brought me to the end of July this year. About five months ago. I got a lot of advice to take some kind of sabbatical, but there was too much going on, and by then, I was way too much of a feminist to be “hushed away” like some pregnant daughter of a socialite. So… we did this staff meeting on a Monday morning, and we’d already arranged for a summer staff party at my house for the following Friday. Everyone said they were still coming. In December, I had made the goal of our holiday party to make them feel safe, to make them feel welcome, and to make them feel like part of the family and not just employees. In July, they returned the favor with interest. And they did so happily. And it was easy.

And here I am. A happy girl, changing the world for kids with autism by day, and the LGBT community by night.

Fast forward five months, and my transition hasn’t cost me anything with my social life – it’s only made it way better. I haven’t lost friends, but I’ve gained a ton. The very worst responses I have have been mildly lacking in understanding. No one calls me names. I walk with confidence. My career hasn’t slowed down any. We still get invited to parties. I’m not saying that this is what happens. But I want to stop, and take a moment, and say that this is what happened. In Grand Rapids. At a Christian Service Agency. Where even the pastors like me. The next staff party I threw (last week) was even bigger yet. And it happened, amazingly, without a clear policy of LGBT workforce inclusion, with offices in the suburbs (where Grand Rapids’ pioneering non-discrimination ordinance doesn’t apply), and with all of us just doing our best to cobble a transition plan together without much experience in doing this. That’s surprising – in fact, we did have one prior transition happen at Hope Network, some years ago, but it did not go very well, and that makes my experience even more surprising.

Back in January, probably the fourth or fifth time I left the house in makeup, a friend called me to go out to an inclusive bar downtown (Pub 43, it’s gone now) on a cold, cold day. My friend can be kind of a downer, so I felt like I had to say yes and reward good behavior. So I put a dress on, and out I went. I walked up the rusty back stairs, trying not to fall in heels. And this person catches my eye, standing with friends, at the top of the fire escape on a smoke break. Wearing a cute little vest, tie, and pocket watch. And opens the door for me. And our eyes meet. And… I’m taken. I wasn’t looking for a woman in my life. I realized in transition I’m mostly attracted to men, which never made sense until I could get my head around the idea of being their girlfriend. But I was also happy single. And yet, here’s this butch. So I bat my eyelashes, get Teri to come over to talk to me and my friends. Turns out she’s a writer. An in. So we talk on Facebook, and I ask to read her writing (oldest trick in the book). And she’s shy, and flirty, but doesn’t ask me out on a date. So I set it up. And she almost doesn’t come – car troubles. So I pick her up. And she seems nervous. So I touch her arm, and there’s electricity. But she runs out of the car when I drop her off, and she doesn’t kiss me, and that hurts. Well, I don’t give up easily. I invite her over. I tell her, “This time, you better kiss me.” And she does. And it’s wonderful. And I can wrap my head around being a lesbian. For her. Except… our relationship doesn’t seem to stay exactly lesbian. It gets way het. She’s my prince charming. I tell her – because we’re kind of crazy about each other, I want to be your wife someday, but it doesn’t feel right, calling you my wife. But I will if that’s what you want, or partner, or what do you want? Later… quite a bit later, I find out what I kind of already knew. Teri entered my life identified as a butch lesbian, but is increasingly identifying as a trans man in queer-safe spaces, with the hopes of doing so everywhere soon. And the thing is, the really crazy thing is, that people get us. I bring him to my work Gala in November, and it’s perfectly natural. He’s chatting up the clergy and one of our board members. We’re a perfectly natural couple. And here I am at our Gala again, for the third time altogether, and for the first time, in a black dress. Which is where I belong, but now also as I belong.

Mad fierce in the photobooth at the Hope Network Annual Gala 2014

And, there it was, my Jane Austen ending starting to come true, after all. So let me use that story as an introduction into the Network. I network by temperament. So I approached transition like everything else – I built a constituency. I gauged supporters. I stacked the deck. During my transition, I wasn’t sure what would happen. We did make a hedge plan, and we almost moved to Houston. But we didn’t, because GR is where we belong. Because my autism team needs me. Because my neighborhood needs me. The Network needed me too, and asked me to join the board.

After I knew I was staying, I accepted. As I did that, I found an organization with a deep history. In 1987, a group from West Michigan went to a historic march on Washington, DC, to press for gay and lesbian rights. They came back from the march energized about sustaining that momentum here in West Michigan. In 1988, we had our first Pride. At its peak, we had probably 13,000 people at Pride. But the organization wasn’t developed or nurtured. By the time I came to it, it was in dire straits. It served maybe 150-200 people in support groups, but it wasn’t really nourishing or growing those groups. It had maybe 7,000 people still coming to Pride, but it had lost the momentum, whereas we could have the biggest pride in Michigan. We hadn’t really grown our activities to celebrate the broader LGBTQIA+ story, either, and we weren’t an effective partner really with anyone. We had a dilapidated membership, a senior leader who did not have the right skill set, and a diminished board, with capable people, but far too few of them.

I’ve turned around engineering projects. I turned around the Center for Autism. So I set to figuring out how to turn around the Network. I did a lot of happy hour conversations and power lunches. I asked a lot of people a lot of questions. And this is what I came up with.

We live in historic times. In 2004, a popular vote amended our constitution to block marriage equality. In 2014, we clearly have a majority on our side. Sure, key leaders in organizations like the Church are against us, but most of their followers are not – the Vatican may not be very LGBT-friendly, but the overwhelming majority of Catholics are. We’ve had recent setbacks, to be sure. Elliott-Larsen was not a victory for us, although we were able to stop MiRFRA in its tracks. But, the first key thing I want you to understand about re-imagining LGBT Community, is that we are on the precipice of a world in which our lives matter, and our loves matter. And that world is about to see just how much our gifts matter. Because we’re out here changing the world, already, just nobody knows it. You know it, if you’ve come to a space like an OutPro event. When you do a 360 in that space, you have to be astonished at the kind of leadership and seniority we’ve achieved across every kind of industry. The truth is, when you look at an OutPro event, you start to wonder how or if Grand Rapids could even run if it didn’t have us. We’ve got a lot to give. We are giving a lot. And we’re not just making the world better or safer for LGBT people. We’re doing it for all of us.

That’s the first thing. The second thing is that, in this world, where our lives increasingly matter, and our loves matter, and we are free to practice our gifts, it is increasingly clear that the gains we have made in the 45 years since Stonewall, have not come for everyone. There’s an ever-larger segment of stories like mine. My board president moved into a small neighborhood of affluent and powerful people. They didn’t just accept him and his husband. Because of him and his family, they came together, and the whole neighborhood is closer than it was before. At the same time, there’s a subset of LGBT people who, if you ask them, would think stories like mine or his are crazy. Because they remain severely marginalized and oppressed. Often, it’s because they are multiply marginalized. They live at the intersection of being LGBT and… being from a marginalized ethnic community, growing up in poverty, surviving abuse/neglect, surviving mental illness, etc., etc. But whatever the cause, they’re being left behind – and that disparity is growing, not shrinking. The things we’ve been doing over almost fifty years, which culminate in unheard of things like the way in which my transition has been received, they are simply not benefitting this subset, and they will predictably continue to not benefit this subset.

It’s the confluence of these two realizations that’s at the core of my proposal to reimagine LGBT community. We have to think about what LGBT community means when many of us are no longer very oppressed. When we have our rights. And we have to think about how we can change the conversation so that the movement benefits not just people like me, but all of us.

The way that I propose to do that – the leap from yesterday’s thinking about LGBT community (which is what I found at the Network), to tomorrow’s thinking, is that we need to be thinking and building, right now, a model of the LGBT community not just as an oppressed, marginalized group, but as a stakeholder minority. In the way that some of our overrepresented ethnic minority groups have done, we want to “flip the script,” and not just keep fighting for our rights, but increasingly showcase our public commitment to building vibrant and dynamic communities that are inclusive not only of us, but of everybody. I believe it’s an approach that’s uniquely suited to West Michigan. As a community, we have conservative values. We believe in economic development as the cornerstone of prosperous communities, and our communities have made key investments to leave behind the comfort of what Holland or Grand Rapids was, 20 or 30 years ago, to embrace having a future. LGBT people have a lot to give in this. And following our over-represented minority group examples, this is how we move our community into a place of entrenchment, where we’re part of the establishment, and we’re not invited to the table for scraps, but because we belong at the table.

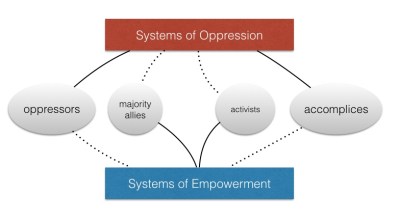

We started on this re-imagining with the Network about two months ago. It’s early yet. But we’re investing in three strategic pillars. First, we’re going to double down on our heritage of Nurturing The Family. This means that we’re going to really enhance our groups, work to increase membership, and work to make sure the map of our groups matches the needs of the community. Right now, we have active groups for LGBT youth, the trans community, cross dressers, men’s and women’s social groups, parent support groups, and a book club. We’re going to add this year, new activities around wellness interventions for the LGBT community (in partnership with MDCH and other community centers), and a new group for people who are LGBT and experiencing mental illness or behavioral health challenges. Brand new is Our Narratives, our new educational program series. The flagship of this is a workshop that we do (actually, at our home), with small groups. We teach a structured format in which people can tell their stories, integrate their stories with the broader struggles of their community, and leverage the impact of their stories to push for change, both large and small. Outcomes data from our first session indicate that, while the people who come to the program know their own identity, they don’t know how their own struggles relate to the broader story of the LGBT community, and they don’t know how to ask for change or feel comfortable doing so. When they leave, they show significant (in one day) increases in these areas. And they’re going to build an army of advocates. We’re just starting. In January, we’re doing So You Want To Be An Ally. It’s every bit as subversive as it sounds. We’re going to make you re-think everything you thought you knew about what it means to be an ally. And when I say you, I mean all of us – because LGBT people act as allies to people in the other letters (just like I’ll never understand what it’s like to be a gay man). But the thing is, a lot of us make pretty bad allies. A lot of the time. We co-opt the movement. We want our voices to be louder than theirs. We set the expectation that the people whose allies we are place our needs above theirs – that they stop talking, and let us advocate for them. We make them stop their conversation and explain themselves to us. Over and over. And we make too many mistakes and show them too little respect. That’s not being an ally. So we’re going to teach all of us what it means to be a real ally. It’s going to be hard, and it’s going to be challenging, but we’re going to build a real Family with deep and strong roots this way.

Second, we’re going to dramatically expand how we think of Celebrating Our Diversity. Pride is a good start. We’ve got one of the best family-friendly Prides in the world. What we do best is something different from San Francisco, but we have an unparalleled space in which we can party and have a good time, out in the open, LGBT and ally like, and right in the heart of our city, where we belong. But we want to have the biggest Pride in Michigan, someday soon (it’s a friendly competition!). Some of you came to Transgender Day of Remembrance, and so this is maybe your second dose of Mira, but this is just the start of what we’re going to do here. We’re going to build a celebratory calendar throughout the year. We’re just getting started with this, and it’ll take time. But we’re going to do more to celebrate more layers of the LGBT community. We’re going to celebrate the layers many people don’t know about yet, like the asexual/aromantic community (or “Aces”). We’re going to celebrate coming out. We’re going to partner, too. Maybe you can help us create an annual event that recognizes the parents who helped make us possible (like my fierce mom!). We’re looking for partnerships to do things like celebrate LGBT figures in different ethnic groups in town, partnerships to recognize LGBT women and the contribution they make to women’s history, or LGBT businesspeople and the contribution they make to the economy, again, in partnership with the mainstream community. We’re going to use each of these events to highlight how the world is a better place not in black and white, but in all the colors of the rainbow.

Finally, we’re going to invest in something brand new, which is a radical new Engaging with Our Community. This will take a little time, but we’re starting to build an LGBT Volunteer Corps. What we’re going to do with it is instill a culture of volunteerism for the broader good, in LGBT people (because LGBT community goes beyond being gay – we’re a group of really great, passionate, engaged people). Already, whenever anything good happens in our cities, you can bet there are LGBT people involved. But no one knows it. In the future, if there’s a river cleanup, if there’s a building project, a neighborhood renovation, I want the community to count on a contingency of people in Network t-shirts to show up, LGBT people and our allies shouldering the burden alongside their neighbors.

And that’s how we win. We build a world that is better for everybody. Rather than responding to negativity from elements in, say, minority faith communities, we show solidarity with their communities, and this calls them out as they are – small minded individuals, not voices for the people. We build a world where people stop thinking of us as the next annoying group we need to give rights to (coming close on our heels, as I understand it, is people who want to marry horses), and instead, they call us when they need buy-in to make something great happen. And we stand hand-in-hand, and our solidarity creates a chain that uses this to lift all our people out, let them all come out of whatever closets they’re in, and let them walk free and proud, where they belong, at the heart of our community.

If we do all this, we don’t just dream of a future where stories like mine aren’t exceptional. We build that future. And we own it. So. That’s what we’ve been up to. That’s how we’re re-imagining LGBT community. And we need your help. We need you to be members – to take a public stand that you are an owner in great LGBT community and in a partnership to build greater, more vibrant communities. You can also support us by coming to our Gala, February 21, tickets on sale at our website, or if you’d like to talk to us about sponsorship opportunities, we have some great ones. As PFLAG, we also want you to be our partners – by finding ways to co-educate or a celebratory event put on in partnership between us.

Thank you so much for your time. Thank you so much for being allies, and for believing.